Understanding Waterborne Diseases in the 19th Century

In an era before modern sanitation and germ theory, waterborne diseases were rampant, devastating cities and villages alike. Below are two of the key illnesses and their impacts:

Cholera

Known as “the blue death,” cholera caused severe dehydration and shock, leaving victims with sunken eyes and blue-tinted skin.

Typhoid Fever

This bacterial infection caused high fever, abdominal pain, and sometimes a distinctive rash.

Waterborne diseases thrived in contaminated rivers, wells, and public water supplies, with little understanding of how to prevent their spread.

Cholera: A Silent Killer Across Centuries

Origins and Early History

Cholera was first documented in South Asia, with records of devastating outbreaks in India. Its connection to contaminated water sources was not yet understood, but the disease’s rapid and deadly impact on communities was evident. In the late 18th century, British colonial administrators in India began chronicling its spread, particularly in the Ganges River Delta, an area notorious for outbreaks due to stagnant and polluted water sources.

The First Cholera Pandemic (1817–1821)

The first cholera pandemic originated in Jessore in the Ganges Delta in August 1817 and moved on to Calcutta (modern-day Kolkata) in September. Its rapid spread along trade routes made it the first truly global pandemic of modern history. Bengal’s waterways facilitated its transmission to Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Africa.

In India alone, millions succumbed to the disease during this period, with millions of deaths recorded between 1817 and 1860. This pandemic also marked the beginning of cholera’s migration westward, setting the stage for future outbreaks in Europe and the Americas.

Spread to Europe and the Americas

Cholera reached Europe in the early 19th century, with the first major epidemic in England occurring in 1831. The disease devastated overcrowded urban areas, especially industrial cities like London, Manchester, and Glasgow, where inadequate sewage systems and contaminated drinking water amplified its spread. By the 1830s, cholera had also crossed the Atlantic, arriving in North America. Major cities like New York and New Orleans experienced outbreaks, with significant mortality rates. These outbreaks underscored the urgent need for public health reforms in both Europe and the Americas.

Symptoms and Physical Impact

Cholera is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae and its nickname, “the blue death,” reflected the stark and gruesome physical changes it inflicted:

- Severe dehydration: Victims quickly lost skin elasticity, their eyes became sunken, and their extremities took on a bluish tint due to circulatory collapse.

- Violent diarrhea and vomiting: Fluid loss could reach 20 liters per day, often described as “rice-water stools” – named for their resemblance to the liquids found in a pot in which rice has been boiled.

- Muscle cramps and extreme exhaustion: The loss of electrolytes caused painful spasms and an inability to move.

- Shock and death: Without rehydration, victims often died within hours.

The speed and severity of the disease terrified communities and overwhelmed physicians, many of whom still believed in the miasma theory, attributing cholera to “bad air” rather than contaminated water.

Key Historical Figures

John Snow (1813 – 1858)

A British physician, Snow is often called the “father of modern epidemiology” for his groundbreaking work during the 1854 cholera outbreak in London. Using maps and statistical analysis, he traced the outbreak to a contaminated public water pump on Broad Street, debunking the miasma theory and proving that cholera spread through water.

Robert Koch (1843 – 1910)

The German microbiologist who identified the bacterium Vibrio cholerae in 1883. Koch’s work in Egypt confirmed cholera as a waterborne bacterial disease, paving the way for modern water treatment methods.

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910)

Though primarily known for her work in nursing, Nightingale advocated for sanitation reforms in hospitals, particularly during the Crimean War. Her efforts highlighted the link between hygiene and the prevention of diseases like cholera.

Edwin Chadwick (1800–1890)

A public health reformer in England, Chadwick’s advocacy for sanitation reforms, including proper sewer systems, helped mitigate cholera outbreaks in urban centers. His work influenced the 1848 Public Health Act, a cornerstone of modern sanitation policy.

Social and Cultural Impacts

Public Panic and Distrust

Cholera outbreaks often led to widespread panic. In many cases, the fear of the disease fueled public distrust of government authorities and medical professionals. In cities like Paris and Naples, rumors circulated that the rich were poisoning the poor’s water supply, leading to riots.

Class Divide

Cholera disproportionately affected the poor, who lived in overcrowded neighborhoods with limited access to clean water. Wealthier citizens, able to flee affected areas or access private water supplies, were less impacted. This divide highlighted the inequalities in urban infrastructure and public health systems.

Religious Interpretation

Many communities saw cholera as divine punishment for moral failings. Religious leaders often called for prayer and repentance rather than advocating for sanitation measures, delaying effective interventions.

Public Health Reforms

Repeated cholera outbreaks in the 19th century spurred significant advancements in public health infrastructure:

- Sewer systems: Cities like London constructed vast underground sewer networks to prevent waste from contaminating drinking water

- Water treatment: Filtration and chlorination became standard practices to ensure safe water supplies

- Quarantine laws: Ports introduced stricter regulations to prevent the disease from entering via ships

Legacy of Cholera Epidemics

The cholera epidemics of the 18th and 19th centuries reshaped global health policy and urban planning. They highlighted the critical importance of clean water and sanitation, setting the stage for modern epidemiology and preventive medicine.

Today, cholera remains a global health concern, particularly in regions without access to clean water. Historical lessons remind us of the importance of vigilance and equity in addressing waterborne diseases.

Typhoid Fever: A Silent Scourge of the 18th Century

Origins and Early History

Typhoid fever (also called enteric fever), caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhimurium, has afflicted humans for centuries, but it became a significant health concern in the 19th century due to expanding urban populations and poor sanitation systems. The disease spreads through contaminated food and water, making it particularly rampant in overcrowded environments where clean water sources were scarce.

Symptoms and Physical Impact

Typhoid fever is characterized by its debilitating progression, often lasting weeks if untreated. Common symptoms included:

- High fever: Persistent and rising, sometimes reaching 104°F (40°C)

- Abdominal pain: Intense cramping, accompanied by bloating

- Severe fatigue and weakness: Making it difficult for sufferers to move or perform daily activities

- Rash: A distinctive “rose spot” rash appeared on the chest and abdomen in some cases

- Confusion and delirium: Mental cloudiness or delirium were late-stage symptoms

- Gastrointestinal issues: Including constipation followed by severe diarrhea in advanced stages

Victims often exhibited gaunt features, sunken eyes, and pale skin, terrifying communities and overwhelming early medical practitioners.

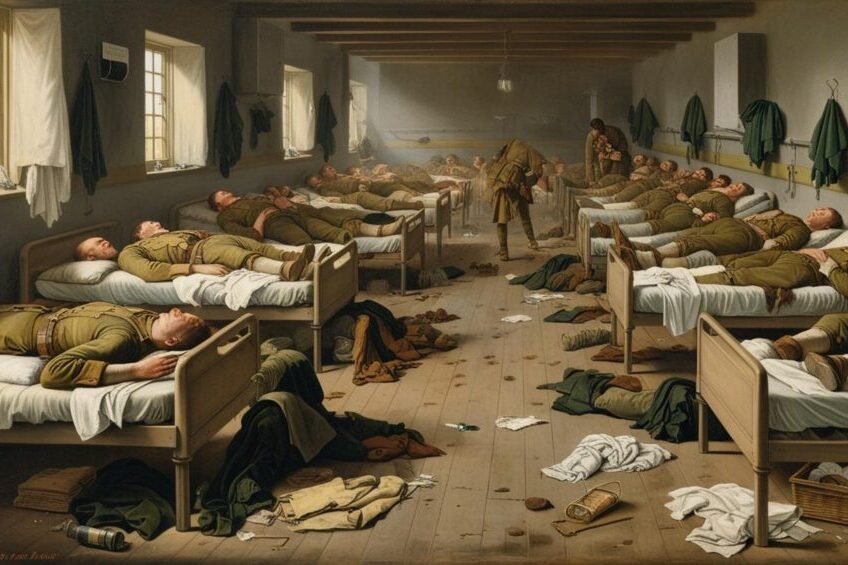

Military Camps and Naval Ships: Hotspots of Disease

Overcrowding and Poor Hygiene

Typhoid fever thrived in military camps and aboard naval ships, where overcrowding and inadequate sanitation created ideal conditions for its spread. Soldiers and sailors often relied on contaminated drinking water and unclean food supplies, exposing them to Salmonella typhi.

The American Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), typhoid fever was a leading cause of death among soldiers. Makeshift camps lacked proper waste disposal systems, contaminating nearby water sources. The disease claimed the lives of countless soldiers on both sides, often weakening entire battalions.

Naval Ships

Naval vessels in the 18th century were particularly vulnerable. Crews lived in cramped quarters with limited access to fresh water, and food stores were often contaminated. Outbreaks of typhoid fever decimated crews, sometimes leading to the loss of entire ships during long voyages.

Urban Centers and Civilian Populations

Inadequate Sanitation

In rapidly growing cities, typhoid fever was a constant threat. Urban centers lacked modern sewer systems, and waste often contaminated public water supplies. Wells, rivers, and communal water sources became breeding grounds for the disease.

Frequent Outbreaks

Though specific records from the 18th century are limited, typhoid fever’s impact on civilian populations was profound. In cities like London, Paris, and Philadelphia, outbreaks often followed periods of heavy rain, which washed human waste into drinking water supplies.

Social and Cultural Impact

Economic Burden

Though specific records from the 18th and 19th century are limited, typhoid fever’s impact on civilian populations was profound. In cities like London, Paris, and Philadelphia, outbreaks often followed periods of heavy rain, which washed human waste into drinking water supplies.

Public Fear

The rapid spread and high mortality of typhoid fever created widespread fear. Like many diseases of the era, it was often attributed to miasma (bad air), leading to ineffective prevention methods. Communities resorted to rituals, religious ceremonies, and other superstitions in the absence of effective medical solutions.

Impact on Families

Typhoid fever was especially devastating to families in lower socioeconomic groups, who were more likely to live in unsanitary conditions. In many cases, entire households succumbed to the disease due to shared water sources and close living quarters.

Medical Understanding and Missteps

Misdiagnosis and Ineffective Treatments

Physicians in the 18th century struggled to differentiate typhoid fever from other diseases, such as dysentery and malaria. Treatments often included bloodletting, purging, and herbal remedies, which were largely ineffective.

Early Observations

While the bacterial cause of typhoid fever (Salmonella typhi) would not be identified until 1880, some physicians began noting its connection to contaminated water and poor hygiene in the 18th century. These early observations laid the groundwork for later public health advancements.

Legacy of 19th-Century Typhoid Fever

Typhoid fever’s devastation in the 18th century highlighted the critical need for sanitation reforms. Though the connection between contaminated water and disease was not fully understood at the time, the outbreaks underscored the importance of clean water and hygiene in preventing illness.

The widespread introduction of clean water and efficient sewer systems in most cities during the late 19th century significantly reduces the threat of typhoid fever in the West. Before an effective vaccine was developed in the late 19th century, first used by the British Army during the Anglo-Boer-War and later by the U.S. Army during World War I, typhoid fever often claimed more lives among soldiers than combat itself.

Today, typhoid fever remains a global health concern, particularly in regions lacking access to clean water and sanitation. Vaccination programs and public health initiatives continue to combat its spread, drawing on the hard-earned lessons of the past. Additionally, it is treatable with antibiotics.